The UN says 75,000 children are at risk of dying of hunger in north-east Nigeria.Open Doors International

The UN says 75,000 children are at risk of dying of hunger in north-east Nigeria.Open Doors International

Seventy-five thousand children are at risk of dying of hunger in north-east Nigeria, reports the UN, as the region deals with the aftermath of Boko Haram violence.

The UN also says that as many as 14 million people are in need of humanitarian aid in that region, the epicentre of the seven-year insurgency which has claimed more than 20,000 lives and displaced more than 2.5 million people in Nigeria and neighbouring countries (Niger, Cameroon and Chad).

The Islamist group captured large parts of Borno, Adamawa and Yobe states in Nigeria’s northeast, and in June 2014 declared a caliphate, with the town of Gwoza as its capital, before being pushed back in recent months.

Christians have paid a particularly heavy price. Open Doors, a global charity which supports Christians under pressure for their faith, estimates that, between 2006 and 2015, at least 15,500 Christians have died in religion-based violence in Nigeria’s north. It also says 13,000 churches were destroyed, abandoned or closed between 2006-14, and that 1.3 million Christians fled to safer regions in the country during that same period.

In 2015-16, the situation worsened as violence spilled over into neighbouring Chad and Cameroon.

In 2014, Boko Haram was named the world’s deadliest terror group, ahead of the self-proclaimed Islamic State, according to the Global Terrorism Index.

“Christians in Borno State are traumatised, displaced and truly they have lost hope. In the Gwoza area there is no single church standing. In the eastern part of Gwoza, Christians were a majority. And even inside Gwoza town, and in its surroundings, there were many Christians. Now there are no Christians left in that area,” Bishop William Naga, leader of the Borno chapter of the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN), told World Watch Monitor.

Many Muslims with views different from Boko Haram’s were also uprooted.

However, Christians who ended up in displacement camps with Muslims say they experienced discrimination there. Bishop Naga explained: “The Borno governor did his best when the Christians had to flee their places in 2014 and 2015. But when the care of the camps was handed over to other organisations, the discrimination started.

“They will give food to the displaced, but if you are a Christian they will not give you food. They will even openly tell you that the relief is not for Christians. There is open discrimination.”

John Gwamma, the chairman at an informal Christian camp, added: “We have started informal, purely Christian camps because Christians were being segregated in the formal camps. They had not been given food, nor allowed to go to church. There is a term called ‘arne’, meaning you are pagan, you are not a Muslim. And as long as you are not a Muslim, they don’t like you to stay together with them.”

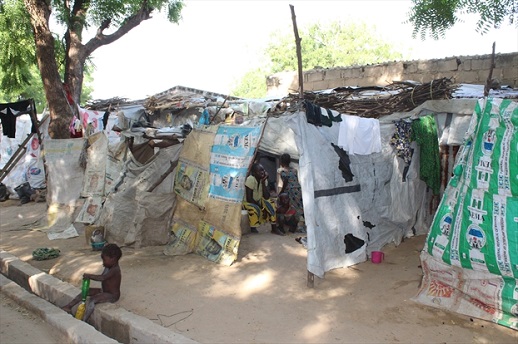

Although the situation across the northeast is dire, circumstances in these informal Christian camps were particularly dreadful. During a recent visit to Maiduguri, workers from Open Doors witnessed how people had resorted to eating leaves.

However, since October the charity has distributed relief packages to 3,000 families – some 15,000 individuals; most of the beneficiaries of the aid were from Gwoza and its surrounding villages. The packages consisted of 100 kilos of maize, 50 kilos of beans, four blankets and some cash to buy oil or soap to help recipients survive for the next few months.

The video below is courtesy of Open Doors.

“We had to flee Boko Haram because they didn’t allow us to go to our farm,” said Mary Charles, one beneficiary. “We had no drinking water and we didn’t have anything to eat. But I take courage from the Bible. It is written that there is a time when we will suffer, but that the suffering will end by the grace of God. We have to endure. I thank God for this food aid and I thank the people who brought it. We now have food that we can give to our children. We didn’t have anything to give them.”

Bishop Naga told World Watch Monitor: “Only the bigger towns are fully under the control of the Nigerian army. The outskirts of these towns and villages in Borno state are not safe. Boko Haram is still in control of big parts of the state. We cannot go back there now. And we fear to live together with our former Muslim neighbours. We don’t know if we can trust them.”

While the north-east remains in the grip of lingering insecurity, there is no hope for an improvement to the humanitarian crisis. Even in the towns to which they have returned, Christians cannot access their outlying farms because of continued Boko Haram activities.

Jack van Tol, Open Doors’ Director for West Africa, said: “Reports reached us through our church networks that many Christians were in dire need of food aid. There seems to be general shortage of food aid in the northeast, and Christians testified they were discriminated against in general camps. Through the churches we were able to assist them.”